The timber railroad bridge was once a common sight across the landscape of North America. For over a century, these wooden structures provided a crucial link in the transportation of goods and people, spanning rivers, canyons, and valleys to connect communities and industries.

The timber railroad bridge was once a common sight across the landscape of North America. For over a century, these wooden structures provided a crucial link in the transportation of goods and people, spanning rivers, canyons, and valleys to connect communities and industries.

Although most of these structures have long since been replaced by modern steel or concrete bridges, the legacy of the timber trestle lives on through photographs and memories.

In this article, we explore the rich history of timber railroad bridges, from their early origins in the 19th century to their eventual decline in the 20th century.

Along the way, we’ll examine the design and construction of these massive wooden structures, the challenges faced by the engineers who built them, and the impact that timber bridges had on the growth of North America’s railroad network.

Accompanying the text are numerous vintage photographs of timber trestles that no longer exist, providing a glimpse into a bygone era of engineering and transportation.

From the towering structures of the Pacific Northwest to the narrow crossings of the Appalachian Mountains, these images offer a fascinating look at the wooden bridges that once spanned the continent.

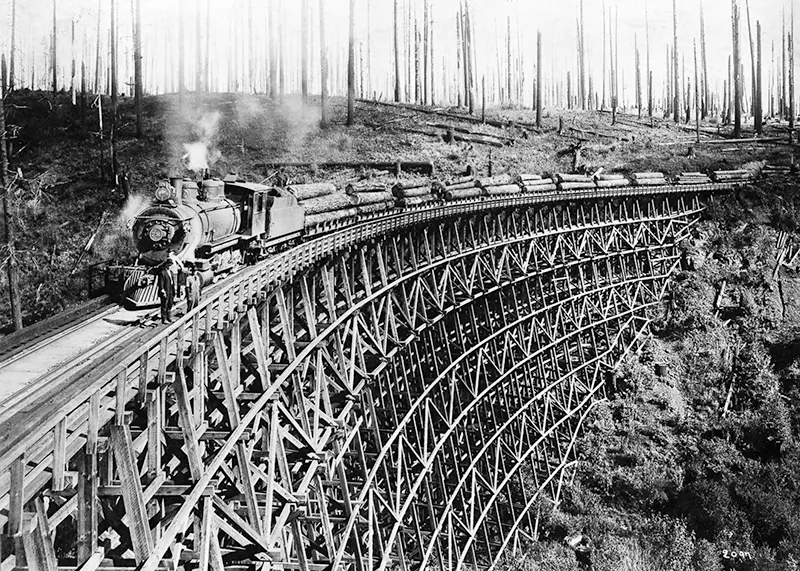

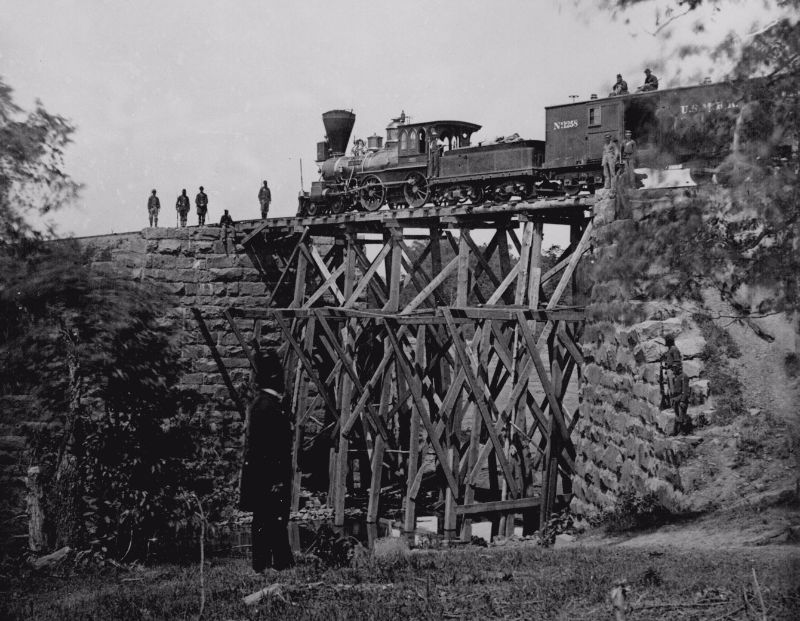

A steam train carrying lumber stops on top of a trestle bridge on a tributary branch of the Northern Pacific Railroad.

Timber trestles were one of the few railroad bridge forms that did not develop in Europe. The reason was that in the United States and Canada, cheap lumber was widespread and readily available in nearby forests.

The Pacific Northwest of the U.S. and the province of British Columbia, Canada became the central region for hundreds of logging railroads whose bridges were almost all made of timber Howe trusses and trestles.

Timber trestles generally come in two forms. The first and most common is the pile trestle which consists of bents spaced 12 to 16 feet apart. Each bent consists of 3 to 5 round timber poles that are pounded straight into the ground by a pile driver.

The center post is upright, the two inner posts are angled at about 5 degrees and the outside posts are usually battered, angling outward for stability at about ten degrees.

During construction, the top of the uneven posts are cut to the proper level for a cap which in turn supports the stringers and planks that hold the rail. Taller pile trestles contain diagonal “X” bracing across one or both sides of the bent and also between bents.

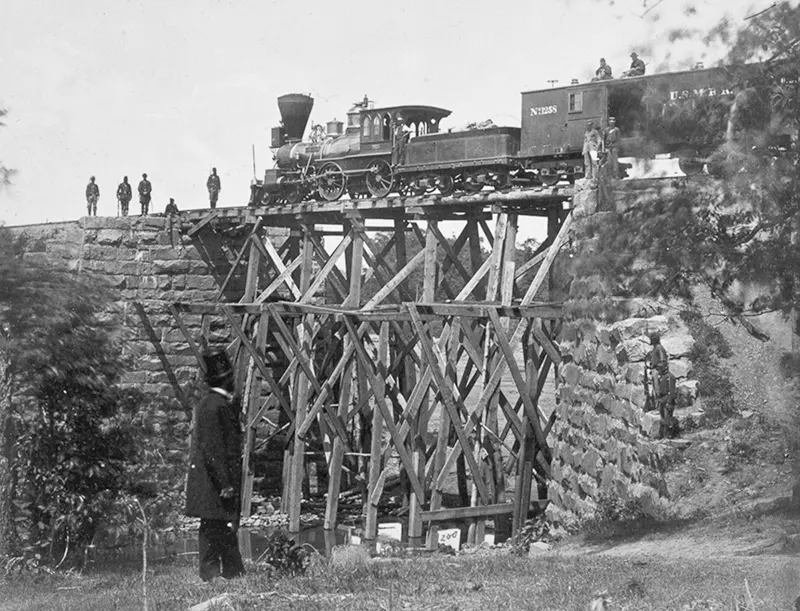

A trestle bridge on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad in Virginia.

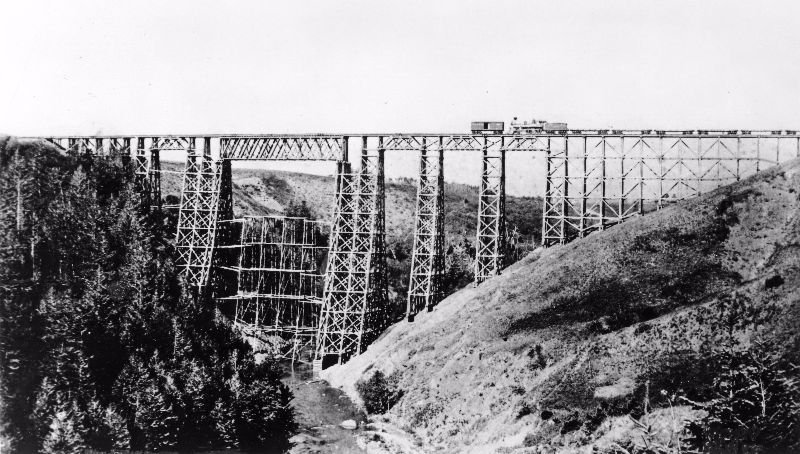

For higher timber trestles, the framed bent is used. Unlike pile bents, frame bents usually use square timbers and rest on mud sills or sub sills that act as a foundation.

Frame bents are built in a series of “stories” that are usually between 10 and 50 feet high. For extremely high trestles, each section of the bent is built flat on the ground as a single or double story and then lifted and placed onto the ever-lengthening trestle.

As railways continued to expand, timber trestles became larger and more complex. Some of the most remarkable timber trestles were built in the early 1900s and were up to 200 feet tall and a quarter-mile long.

The Camas Prairie Railroad in northern Idaho utilized many timber trestles across the rolling Camas Prairie and in the major grade, Lapwai Canyon.

The 1,490-foot (450 m) viaduct across Lawyers Canyon was the exception, constructed of steel and 287 feet (87 m) in height.

People sit on the front of a logging train as it crosses a trestle bridge in the Cascade Mountains in Oregon.

One of the longest trestle spans created was for railroad traffic crossing the Great Salt Lake on the Lucin Cutoff in Utah. It was replaced by a fill causeway in the 1960s, and is now being salvaged for its timber.

A coal trestle is a rigid-frame trestle supporting train tracks above chutes, used to deliver fuel to boats or trains beneath it.

At the top of the trestle, rolling stock (typically hopper cars) open doors on their undersides or on their sides to discharge cargo.

Coal trestles were also used to transfer coal from mining railroads to rail cars. They were prominent when coal was an important fuel for rail locomotion and steamships, before they were replaced with mechanical coal loaders during the 20th century.

Coal trestles were used in the Great Lakes ports of Buffalo (on Lake Erie), Sodus Point and Oswego, New York (both on Lake Ontario).

The floodway of the Bonnet Carré Spillway in St. Charles Parish, Louisiana, is crossed by three wooden trestles each over 1.5 miles (2.4 km) in length. The trestles are owned by the Canadian National Railway (two trestles) and the Kansas City Southern Railroad.

The trestles were completed in 1936, after construction of the Spillway. The trestles may be the longest wooden railroad trestles remaining in regular use in North America.

A locomotive engine pushes two open cars across a newly assembled railroad trestle in order to test it.

Despite their impressive size, timber trestles were not designed to last forever. They had a limited lifespan due to the decay of the wood and the constant exposure to the elements.

Untreated lumber only lasted about 20 years and locomotives could easily cause the wood to catch fire. Collapses were a regular trestle bridge occurrence on logging railroads and there are numerous accounts of train crews that regularly hopped off their slow moving locomotive as it approached a high, untrustworthy trestle, allowing it to cross before they would then run across the bridge and jump back on.

On main lines that carried passengers and freight, tall timber bridges reduced efficiency as trains had to cross them at slower speeds.

Today, many timber trestles have been replaced with more modern structures made from steel or concrete. However, some timber trestles still remain and are maintained as historical landmarks.

These structures serve as a reminder of the significant role that timber trestles played in the development of rail transportation in North America.

A train passes over the Valley Trestle Bridge Chicago & North Western Railway viaduct over the Des Moines River, near Boone, Iowa.

A freight train moving on a high trestle with two men standing on the roof of one of the cars, 1895

Log bridge (crib trestle) on the Columbia and Nehalem Valley Railroad, Columbia County, Oregon.

Crib trestle bridge of the Columbia& Nehalem Valley Railroad at the McBride Creek, circa 1905.

Montana’s massive 214 foot high Two Medicine Creek timber trestle on the Great Northern Railway.

A home-made log bridge. The men sitting atop it give an idea of its height, and the diameter of the redwood logs used for construction.

A 203-foot high wall of wood — the Cedar River Logging Trestle in Washington State.

A timber trestle over the Crooked River Gorge in central Oregon sits nearly 320 feet off of the water.

Trestle in Central Pacific Railroad, circa 1869.

A spectacular avalanche , Feb 10, 1903 swept away part of a trestle 300 feet high that let northern pacific railway trains descend from this pass since 1890.

Trestle and logging railroad at Robinson’s camp, Clallam County, Washington.

The engine “Firefly” on a trestle of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, circa 1864.

The Dale Creek Bridge, 2 miles west of Sherman, Wyoming.

Trestle construction.

Erie – Constructing Trestle over B&S Railroad.

Erie trestle construction.

Myra Canyon Trestle Bridge near Kelowna, British Columbia. Constructed by Kettle Valley Railway.

The Myra Canyon trestles – located near the city of Kelowna, British Columbia – were constructed by the Kettle Valley Railway (“KVR”), a subsidiary of the Canadian Pacific Railway, as part of a secondary main line route that operated across southern British Columbia.

The Cedar River logging trestle, 203 feet high & 843 feet long, in Washington State, ca. 1917. (Photo by Darius Kinsey).

Another view of the Cedar River logging trestle.