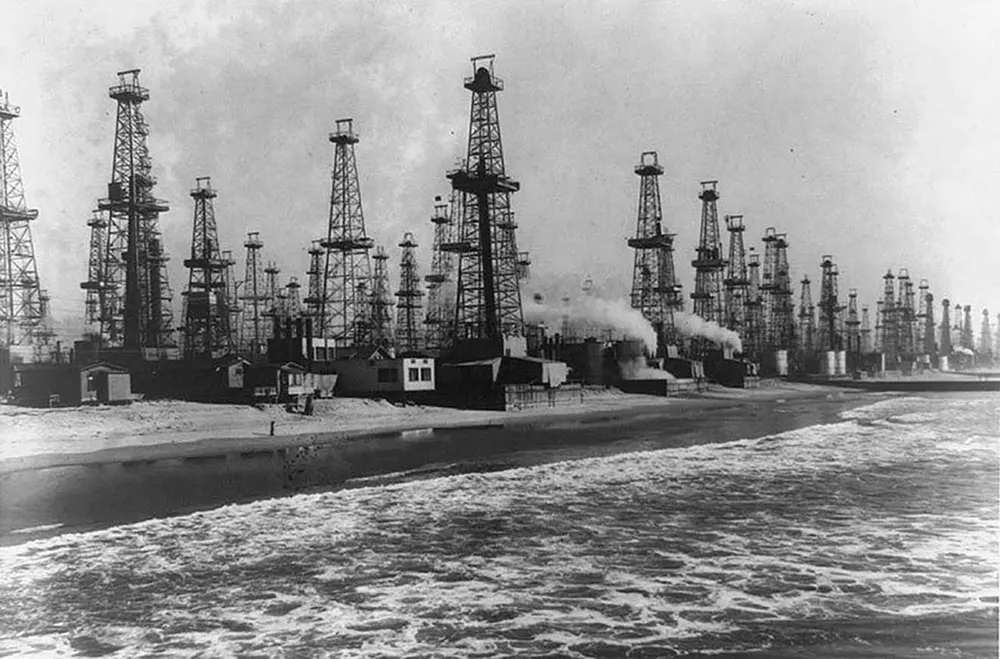

Oil derricks line the coast of Venice, California. 1920.

The Golden State got its nickname from the Sierra Nevada gold that lured so many miners and settlers to the West, but California has earned much more wealth from so-called “black gold” than from metallic gold.

When Europeans finally arrived in California, petroleum had already been in use by Native Americans for about 13,000 years, and they relied on its utility albeit not for energy sources. Natives used oil primarily as a lubricant, but they also used it as a sealant to waterproof canoes.

The first Californian well was drilled in 1865 in Humboldt County. The state’s first gusher arrived in 1876 in the Pico Canyon oil field located north of Los Angeles and launched a statewide industry.

Following the initial oil discovery in California, Edward L. Doheny struck the massive Los Angeles oilfield in 1892, only 35 miles south of the Pico Canyon.

The main character of the 2007 award-winning film “There Will Be Blood” is said to be loosely based on Doheny. In 1897 the world’s first offshore well was drilled from a 300 ft long pier in the Pacific Ocean initiating an offshore drilling boom.

The discovery of oil in California had a significant impact on the price of oil—both in the state of California and across America. In 1860, 0.5 million barrels of oil were produced throughout the country.

By 1895, the state of California, alone, produced 1.2 million barrels of oil. With the new oil supplies from California—along with increased oil production in Texas and Pennsylvania—the price decreased from $9.60 per barrel in 1860 to $0.25 per barrel in 1895.

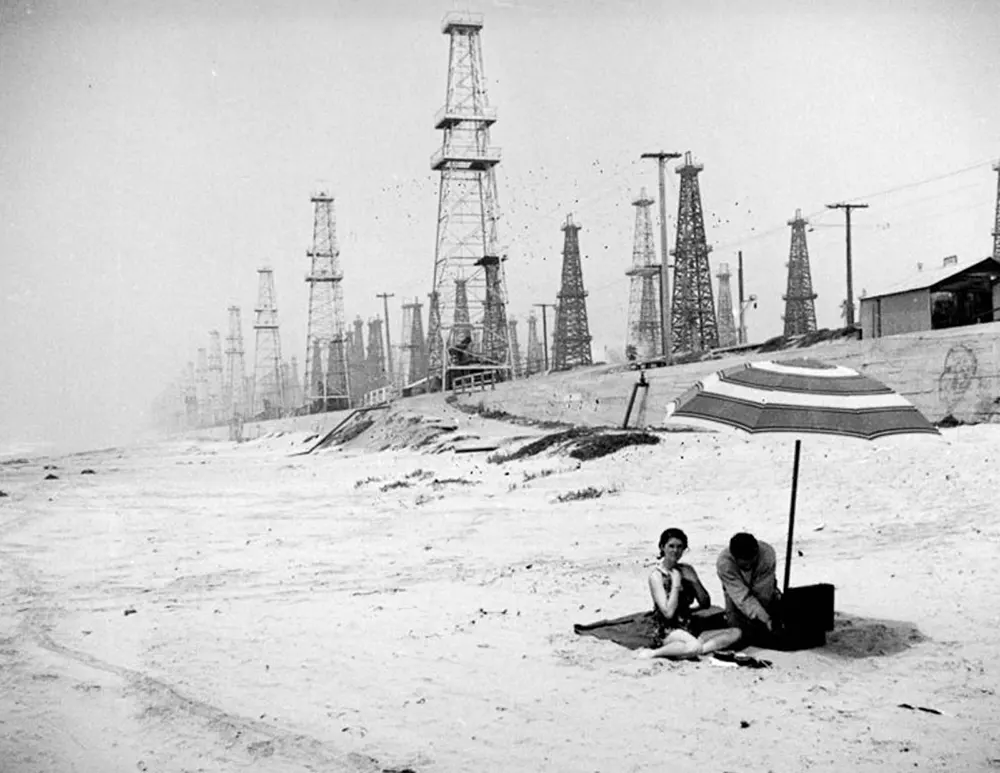

Huntington Beach, circa 1930s.

At the turn of the century, oil production in California continued to rise at a booming rate. In 1900, the state of California produced 4 million barrels. In 1920, production had expanded to 77 million barrels.

Between 1920 and 1930, new oil fields across Southern California were being discovered with regularity including Huntington Beach in 1920, Long Beach and Santa Fe Springs in 1921, and Dominguez in 1923, and Inglewood in 1924. Southern California had become the hotbed for oil production in the United States.

The oil boom caused whole areas to become home to hundreds of wooden drilling derricks owned by independent speculators. With the oil derricks sticking up like giant quills, neighborhoods started to look gloomy.

In places such as Venice, California (now known as Marina del Rey), oil derricks ran right up to the shore, mingling with residential neighborhoods and pristine beaches.

In Huntington Beach and in Santa Barbara, legions of derricks lined the coast, vying for space with sunbathers and lifeguard stands. While today these violent protrusions are at odds with the Southland’s idyllic, fun-in-the-sun image, but at the time L.A. was still in its infancy, and the metastasizing cityscape was preoccupied with growth, not beauty.

This is how Los Angeles Times described the Venice Beach–Del Rey oil field in 1930: Today oil derricks stand like trees in a forest… . Steam pile drivers roar on many a vacant lot… . One hundred and eighty permits to drill for oil have been given and twenty-five more are in procedure… . If this fever continues, as it gives every indication of doing, one reasonably may expect to see virtually the entire water-front line of private properties from Washington street to Sixty-sixth avenue or Playa del Rey dotted with a line of oil derricks.

An oilfield in Venice, California. 1930.

The development of increased oil production in California had other consequences as well. The additional California oil fields—along with booming oil supplies in Texas from Spindletop—resulted in another surplus of oil reaching the market, again impacting the price of the commodity.

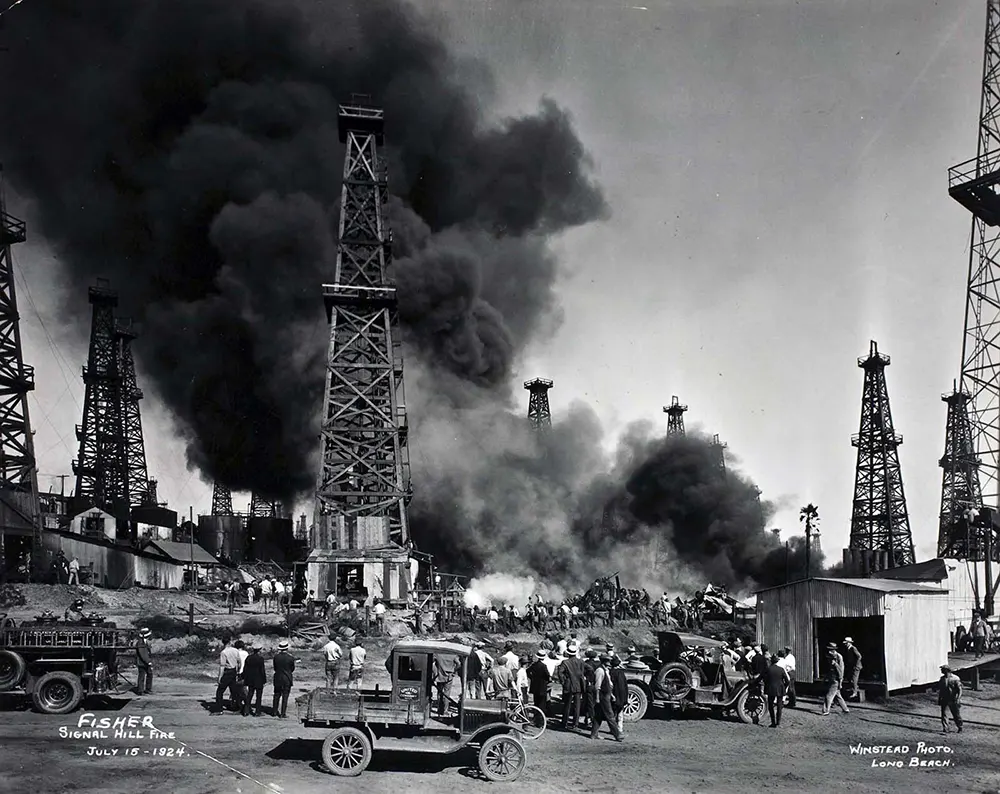

With the accelerated oil drilling, the price of oil in the 1920s fell from $28 per barrel to below $10 per barrel. The issue became an increasingly debated topic in the American economy and political arena.

In 1924, President Calvin Coolidge created the Federal Oil Conservation Board in an effort to control oil production and stabilize the oil market.

However, the American Petroleum Institute (API), representing over 500 oil companies, opposed the program because it feared many of its affiliated oil corporations would go out of business. Ultimately, through API’s resistance, Coolidge’s program never gained sufficient power.

A forest of oil derricks sprouts up on the Signal Hill oil field, Long Beach, California, in 1937.

A man poles a garbage scow down the Grand Canal in Venice, California, with oil derricks on the horizon. 1953.

A high tide floods an oilfield in Long Beach, California. 1951.

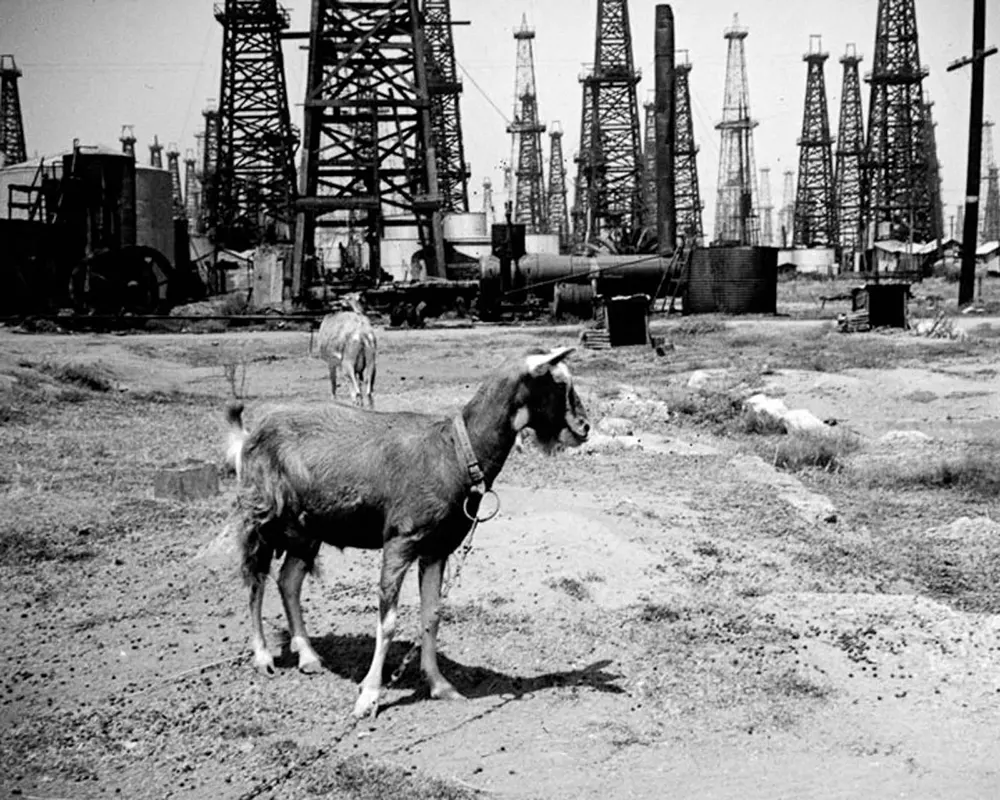

Goats near an oilfield in Huntington Beach. 1937.

Sunnyside Cemetery in Long Beach. 1937.

A family beach picnic with Signal Hill oil derricks in the background. 1920.

Oil derricks on Huntington Beach. 1937.

An oil derrick abuts a beach house in Venice. 1937.

Cars travel through the Venice oilfield. 1937.

Students practice archery at Beverly Hills High School, with oil derricks nearby.

Laundry dries on a clothesline near the Venice oilfield.

A couple on Huntington Beach. 1937.

Oil derricks and bathers on Huntington Beach. 1937.

The Signal Hill oilfield in southern California. 1930.

Sunbathers on Huntington Beach. 1937.

The coast along the Venice oilfield, in what is now Marina del Rey. 1937.

Germany races Italy in the Long Beach Marine Stadium during the 1932 Olympic Games. 1932.

Four boats race in the Long Beach Marine Stadium during the 1932 Olympic Games. 1932.

A Long Beach home with oil derricks nearby. 1929.

Men play volleyball on the beach next to the Venice oilfield. 1937.

Oil derricks loom behind St. Mary’s by the Sea Catholic Church in Huntington Beach. 1937.

Mrs. W. B. Stoddard stands with her dogs in the yard of her home near the George K. Linderman well in Redondo Beach. 1936.

Oil derricks line a road outside Los Angeles. 1930.

Oil wells near La Habra, Orange County, 1920s.

Oil derricks extending into the Pacific at Summerland Beach near Santa Barbara. 1903.

Oil fire on Signal Hill, July 15, 1924.

Oil derrick camouflaged as Christmas tree, Huntington Beach, 1939.

Atlantic Avenue and Patterson Street, Long Beach, are lined with oil derricks in 1940.

Oil wells in Venice, California, bringing oil up from beach area in 1952.

Huntington Beach in the 1960s was riddled with wooden oil derricks.