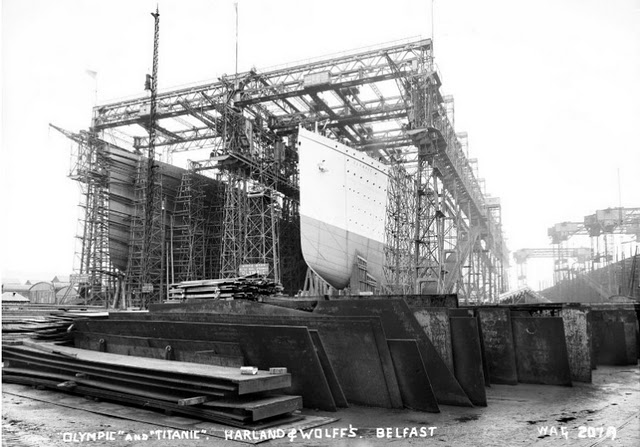

The name Titanic derives from the Titans of Greek mythology. Built in Belfast, Ireland, in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, RMS Titanic was the second of the three Olympic-class ocean liners—the first was RMS Olympic and the third was HMHS Britannic.

The name Titanic derives from the Titans of Greek mythology. Built in Belfast, Ireland, in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, RMS Titanic was the second of the three Olympic-class ocean liners—the first was RMS Olympic and the third was HMHS Britannic.

Britannic was originally to be called Gigantic and was to be over 1,000 feet (300 m) long. They were by far the largest vessels of the British shipping company White Star Line’s fleet, which comprised 29 steamers and tenders in 1912.

The company sought an upgrade in their fleet primarily in response to the Cunard giants but also to replace their oldest pair of passenger ships still in service, being RMS Teutonic of 1889 and RMS Majestic of 1890.

Teutonic was replaced by Olympic while Majestic was replaced by Titanic. Majestic would be brought back into her old spot on White Star Line’s New York service after Titanic’s loss.

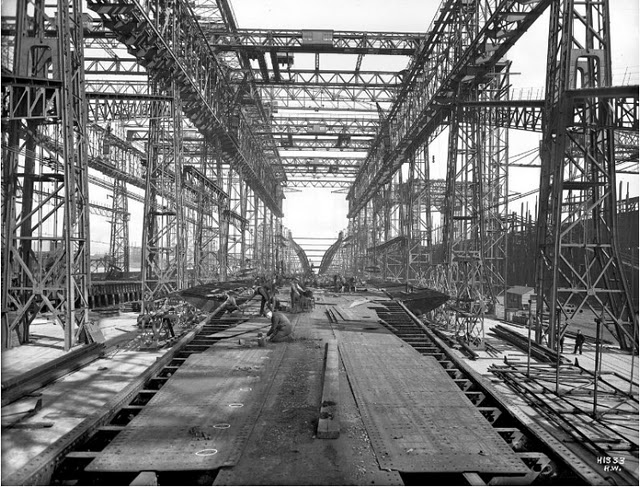

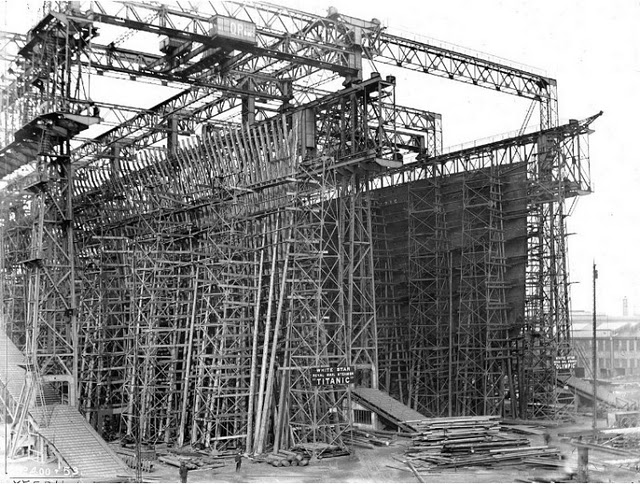

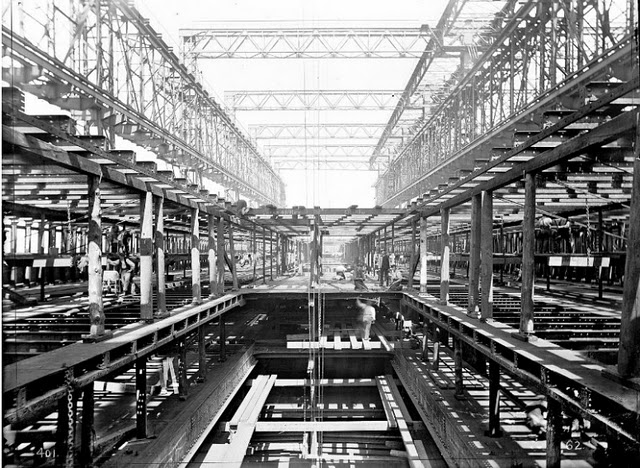

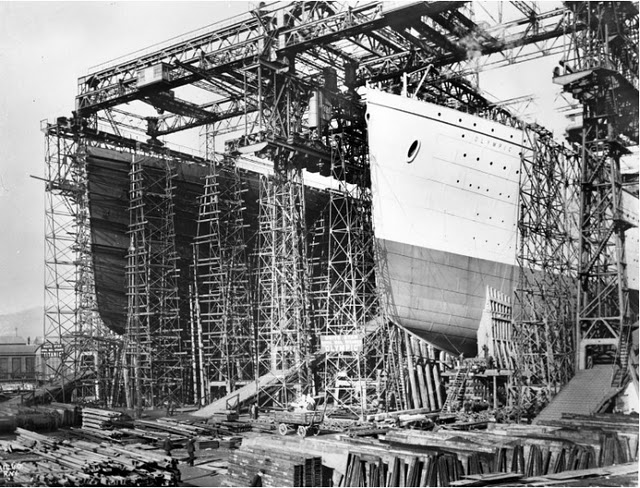

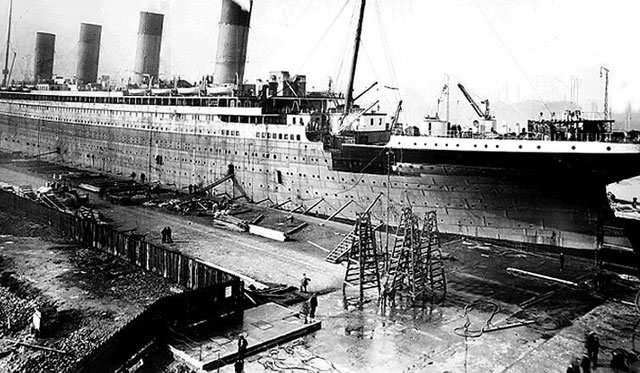

.jpg) The ships were constructed by the Belfast shipbuilders Harland and Wolff, who had a long-established relationship with the White Star Line dating back to 1867.

The ships were constructed by the Belfast shipbuilders Harland and Wolff, who had a long-established relationship with the White Star Line dating back to 1867.

Harland and Wolff were given a great deal of latitude in designing ships for the White Star Line; the usual approach was for the latter to sketch out a general concept which the former would take away and turn into a ship design.

Cost considerations were relatively low on the agenda and Harland and Wolff was authorized to spend what it needed on the ships, plus a five percent profit margin.

In the case of the Olympic-class ships, a cost of £3 million (approximately £310 million in 2019) for the first two ships was agreed plus “extras to contract” and the usual five percent fee.

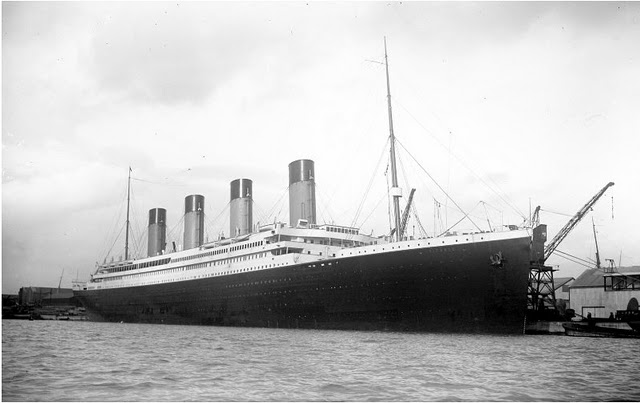

Titanic was 882 feet 9 inches (269.06 m) long with a maximum breadth of 92 feet 6 inches (28.19 m).

Titanic was 882 feet 9 inches (269.06 m) long with a maximum breadth of 92 feet 6 inches (28.19 m).

Her total height, measured from the base of the keel to the top of the bridge, was 104 feet (32 m).

She measured 46,329 GRT and 21,831 NRT and with a draught of 34 feet 7 inches (10.54 m), she displaced 52,310 tons. All three of the Olympic-class ships had ten decks (excluding the top of the officers’ quarters), eight of which were for passenger use. The Boat Deck, on which the lifeboats were housed. It was from here during the early hours of 15 April 1912 that Titanic’s lifeboats were lowered into the North Atlantic.

The Boat Deck, on which the lifeboats were housed. It was from here during the early hours of 15 April 1912 that Titanic’s lifeboats were lowered into the North Atlantic.

The bridge and wheelhouse were at the forward end, in front of the captain’s and officers’ quarters. The bridge stood 8 feet (2.4 m) above the deck, extending out to either side so that the ship could be controlled while docking. The wheelhouse stood within the bridge.

The entrance to the First Class Grand Staircase and gymnasium were located midships along with the raised roof of the First Class lounge, while at the rear of the deck were the roof of the First Class smoke room and the relatively modest Second Class entrance.

The wood-covered deck was divided into four segregated promenades: for officers, First Class passengers, engineers, and Second Class passengers respectively. Lifeboats lined the side of the deck except in the First Class area, where there was a gap so that the view would not be spoiled.

A Deck, also called the Promenade Deck, extended along the entire 546 feet (166 m) length of the superstructure. It was reserved exclusively for First Class passengers and contained First Class cabins, the First Class lounge, smoke room, reading and writing rooms and Palm Court.

A Deck, also called the Promenade Deck, extended along the entire 546 feet (166 m) length of the superstructure. It was reserved exclusively for First Class passengers and contained First Class cabins, the First Class lounge, smoke room, reading and writing rooms and Palm Court.

B Deck, the Bridge Deck, was the top weight-bearing deck and the uppermost level of the hull. More First Class passenger accommodations were located here with six palatial staterooms (cabins) featuring their own private promenades.

On Titanic, the À La Carte Restaurant and the Café Parisien provided luxury dining facilities to First Class passengers. Both were run by subcontracted chefs and their staff; all were lost in the disaster. The Second Class smoking room and entrance hall were both located on this deck.

The raised forecastle of the ship was forward of the Bridge Deck, accommodating Number 1 hatch (the main hatch through to the cargo holds), numerous pieces of machinery and the anchor housings.

Aft of the Bridge Deck was the raised Poop Deck, 106 feet (32 m) long, used as a promenade by Third Class passengers. It was where many of Titanic’s passengers and crew made their last stand as the ship sank. The forecastle and Poop Deck were separated from the Bridge Deck by well decks.

C Deck, the Shelter Deck, was the highest deck to run uninterrupted from stem to stern. It included both well decks; the aft one served as part of the Third Class promenade.

C Deck, the Shelter Deck, was the highest deck to run uninterrupted from stem to stern. It included both well decks; the aft one served as part of the Third Class promenade.

Crew cabins were housed below the forecastle and Third Class public rooms were housed below the Poop Deck. In between were the majority of First Class cabins and the Second Class library.

D Deck, the Saloon Deck, was dominated by three large public rooms—the First Class Reception Room, the First Class Dining Saloon, and the Second Class Dining Saloon.

An open space was provided for Third Class passengers. First, Second and Third Class passengers had cabins on this deck, with berths for firemen located in the bow.

It was the highest level reached by the ship’s watertight bulkheads (though only by eight of the fifteen bulkheads).

E Deck, the Upper Deck, was predominantly used for passenger accommodation for all three classes plus berths for cooks, seamen, stewards, and trimmers.

E Deck, the Upper Deck, was predominantly used for passenger accommodation for all three classes plus berths for cooks, seamen, stewards, and trimmers.

Along its length ran a long passageway nicknamed Scotland Road, in reference to a famous street in Liverpool. Scotland Road was used by Third Class passengers and crew members.

F Deck, the Middle Deck, was the last complete deck and mainly accommodated Second and Third Class passengers and several departments of the crew. The Third Class dining saloon was located here, as were the swimming pool, Turkish bath, and kennels.

G Deck, the Lower Deck, was the lowest complete deck that carried passengers, and had the lowest portholes, just above the waterline.

The squash court was located here along with the traveling post office where letters and parcels were sorted ready for delivery when the ship docked. Food was also stored here. The deck was interrupted at several points by orlop (partial) decks over the boiler, engine, and turbine rooms.

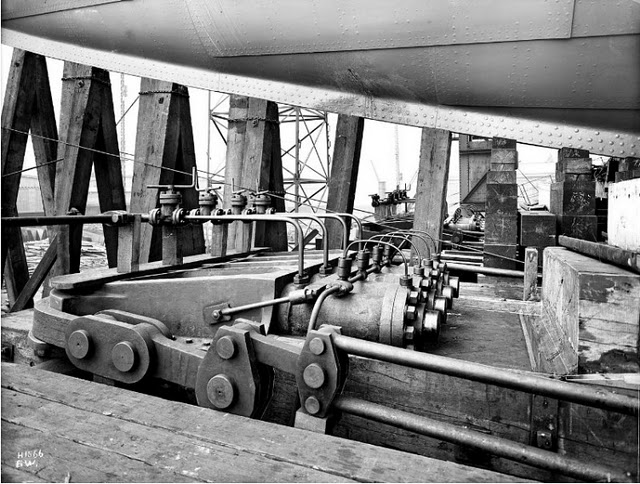

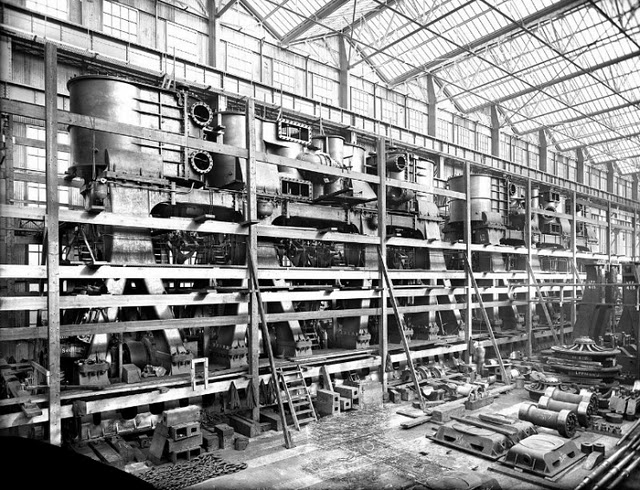

The Orlop Decks and the Tank Top below that were on the lowest level of the ship, below the waterline. The orlop decks were used as cargo spaces, while the Tank Top—the inner bottom of the ship’s hull—provided the platform on which the ship’s boilers, engines, turbines and electrical generators were housed.

The Orlop Decks and the Tank Top below that were on the lowest level of the ship, below the waterline. The orlop decks were used as cargo spaces, while the Tank Top—the inner bottom of the ship’s hull—provided the platform on which the ship’s boilers, engines, turbines and electrical generators were housed.

This area of the ship was occupied by the engine and boiler rooms, areas which passengers would have been prohibited from seeing. They were connected with higher levels of the ship by flights of stairs; twin spiral stairways near the bow provided access up to D Deck.

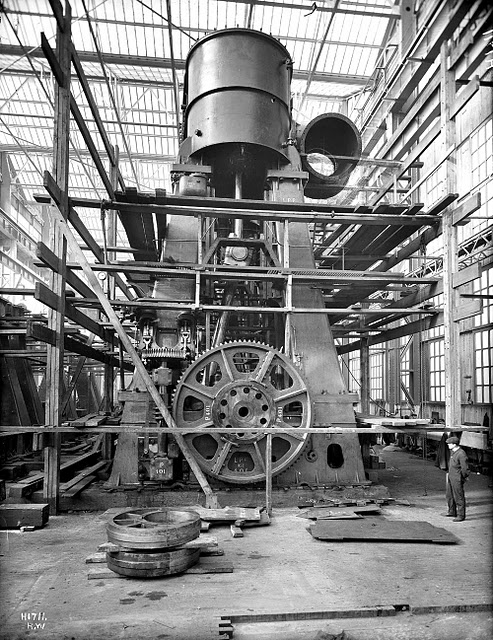

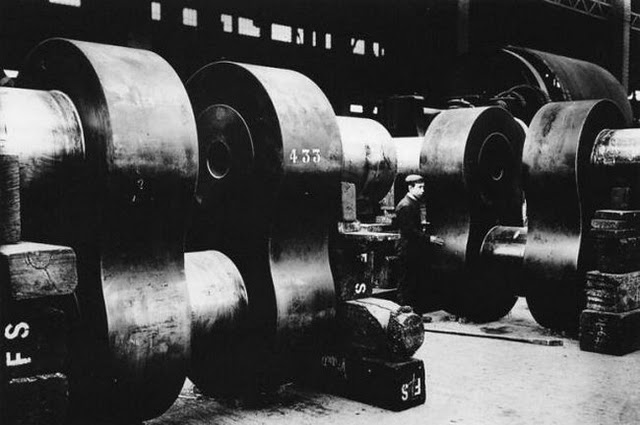

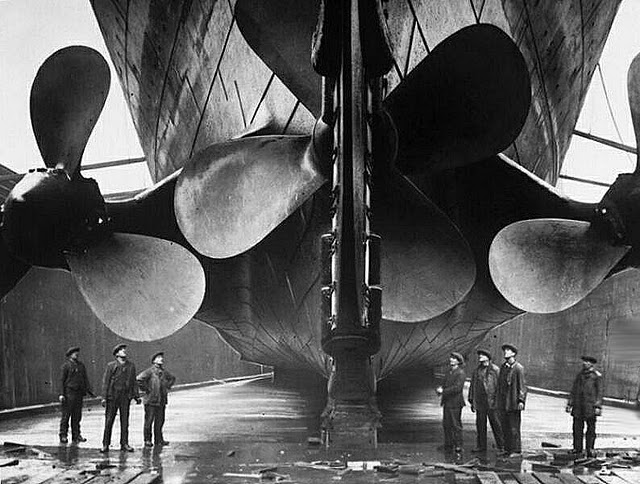

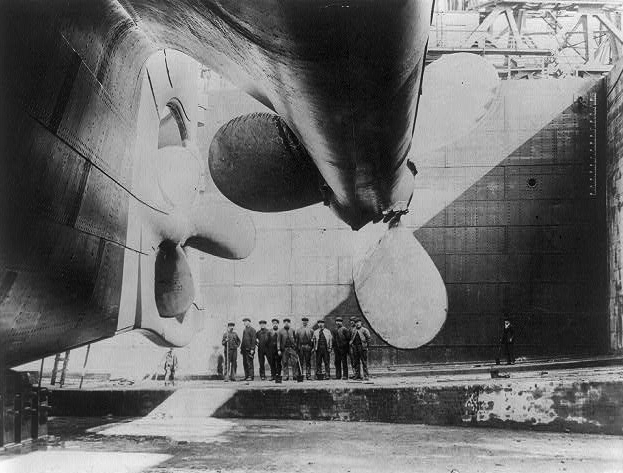

Titanic was equipped with three main engines—two reciprocating four-cylinder, triple-expansion steam engines and one centrally placed low-pressure Parsons turbine—each driving a propeller.

Titanic was equipped with three main engines—two reciprocating four-cylinder, triple-expansion steam engines and one centrally placed low-pressure Parsons turbine—each driving a propeller.

The two reciprocating engines had a combined output of 30,000 horsepower (22,000 kW). The output of the steam turbine was 16,000 horsepower (12,000 kW).

The White Star Line had used the same combination of engines on an earlier liner, Laurentic, where it had been a great success.

It provided a good combination of performance and speed; reciprocating engines by themselves were not powerful enough to propel an Olympic-class liner at the desired speeds, while turbines were sufficiently powerful but caused uncomfortable vibrations, a problem that affected the all-turbine Cunard liners Lusitania and Mauretania.

By combining reciprocating engines with a turbine, fuel usage could be reduced and motive power increased, while using the same amount of steam.

The two reciprocating engines were each 63 feet (19 m) long and weighed 720 tons, with their bedplates contributing a further 195 tons.

The two reciprocating engines were each 63 feet (19 m) long and weighed 720 tons, with their bedplates contributing a further 195 tons.

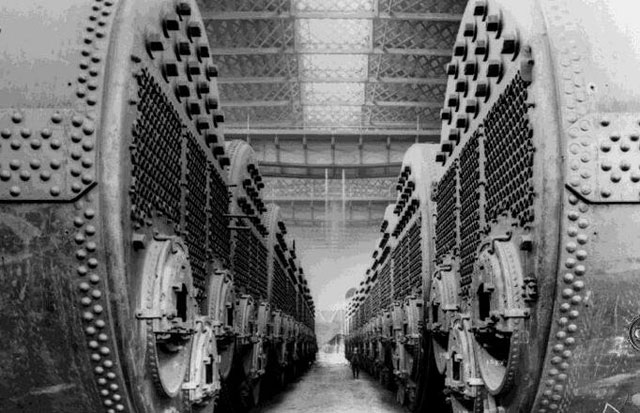

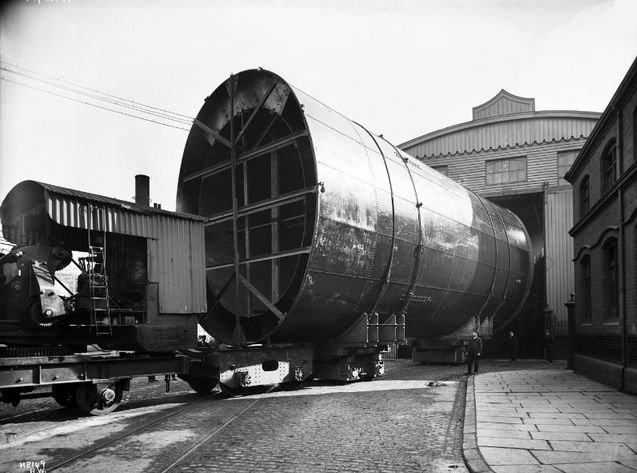

They were powered by steam produced in 29 boilers, 24 of which were double-ended and five single-ended, which contained a total of 159 furnaces.

The boilers were 15 feet 9 inches (4.80 m) in diameter and 20 feet (6.1 m) long, each weighing 91.5 tons and capable of holding 48.5 tons of water.

They were heated by burning coal, 6,611 tons of which could be carried in Titanic’s bunkers, with a further 1,092 tons in Hold 3.

The furnaces required over 600 tons of coal a day to be shovelled into them by hand, requiring the services of 176 firemen working around the clock. 100 tons of ash a day had to be disposed of by ejecting it into the sea.

The work was relentless, dirty and dangerous, and although firemen were paid relatively generously, there was a high suicide rate among those who worked in that capacity.

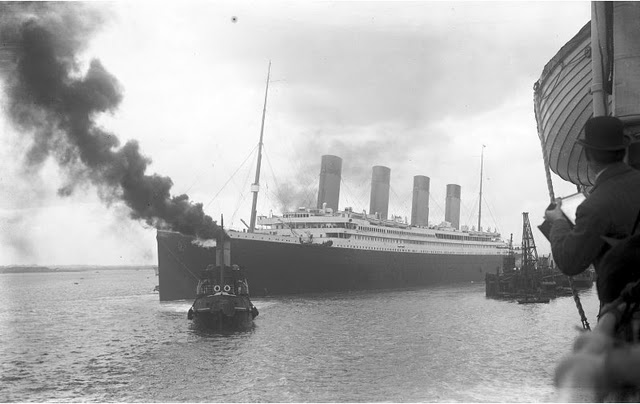

Titanic sank on 15 April 1912 after striking an iceberg during her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York City, United States.

Titanic sank on 15 April 1912 after striking an iceberg during her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York City, United States.

Of the estimated 2,224 passengers and crew aboard, more than 1,500 died, making it the deadliest sinking of a single ship up to that time.

It remains the deadliest peacetime sinking of a superliner or cruise ship. The disaster drew public attention, provided foundational material for the disaster film genre, and has inspired many artistic works.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Flickr).